#9: Rebuilding the self in defiance of caste, one word at a time

“Non-dalits may find it unbelievable, but death for Dalits is metaphorical. An "unto

uchable" never existed as a person worthy of respect from society or recognised as a mind. He was simply invisible, except when his labour was extracted, exploited and used for free… Their actual death lies in an inability to be in text, or transform into a text as a story, memory and history.”

Yogesh Maitreya, water in broken pot

“Anything dead coming back to life hurts.”

Beloved, Toni Morrison.

In an abstract way, I knew that caste and caste-based discrimination was an evil that we need to be rid of. I read and was inspired by the sanitized stories of Babasaheb Ambedkar. I watched and was moved by films like Jai Bhim Comrade, Sairaat, and Fandry.1

But in a few days, I was able to compartmentalize these harsh realities in my mind and get back to shopping in fancy malls, drinking in breweries, watching films in air-conditioned movie theaters and worrying about my EMIs.

Maybe somewhere down the line, I accepted that caste, while cruel and dehumanizing, was a stubborn reality that cannot be gotten rid of, ever. It was this “That’s just the way things are,” thinking that desensitized myself to the caste and atrocities that came with it for Dalits and Bahujans.

But what about those that do not have that luxury? I knew that I needed to educate myself beyond the stray news article. This is where I resolved to understand more about caste through Dalit literature, and start with familiar territory: memoir and fiction.

All the works I have read so far2 unsettled me in the way that caste and the problems it brings should. Each of them shared their raw experiences that broke down the psychic barriers and apathy around the nefariousness of the caste system.

It was Yogesh Maiterya’s water in a broken pot however, that compelled me to write about it first. There are many reasons for this: The fact that he is living in the same age as I was, so caste could not snake itself as a foreign concept of the past in my imagination. He was someone who I had communicated with in person, so there was a sense of immediacy that this is actually happening to someone I know in real life. Most of all, what moved me was his passion for language, books, writing and critical thinking. It reminded me of the true power of stories, and the political charge that they bring, whether we choose to acknowledge it or not.

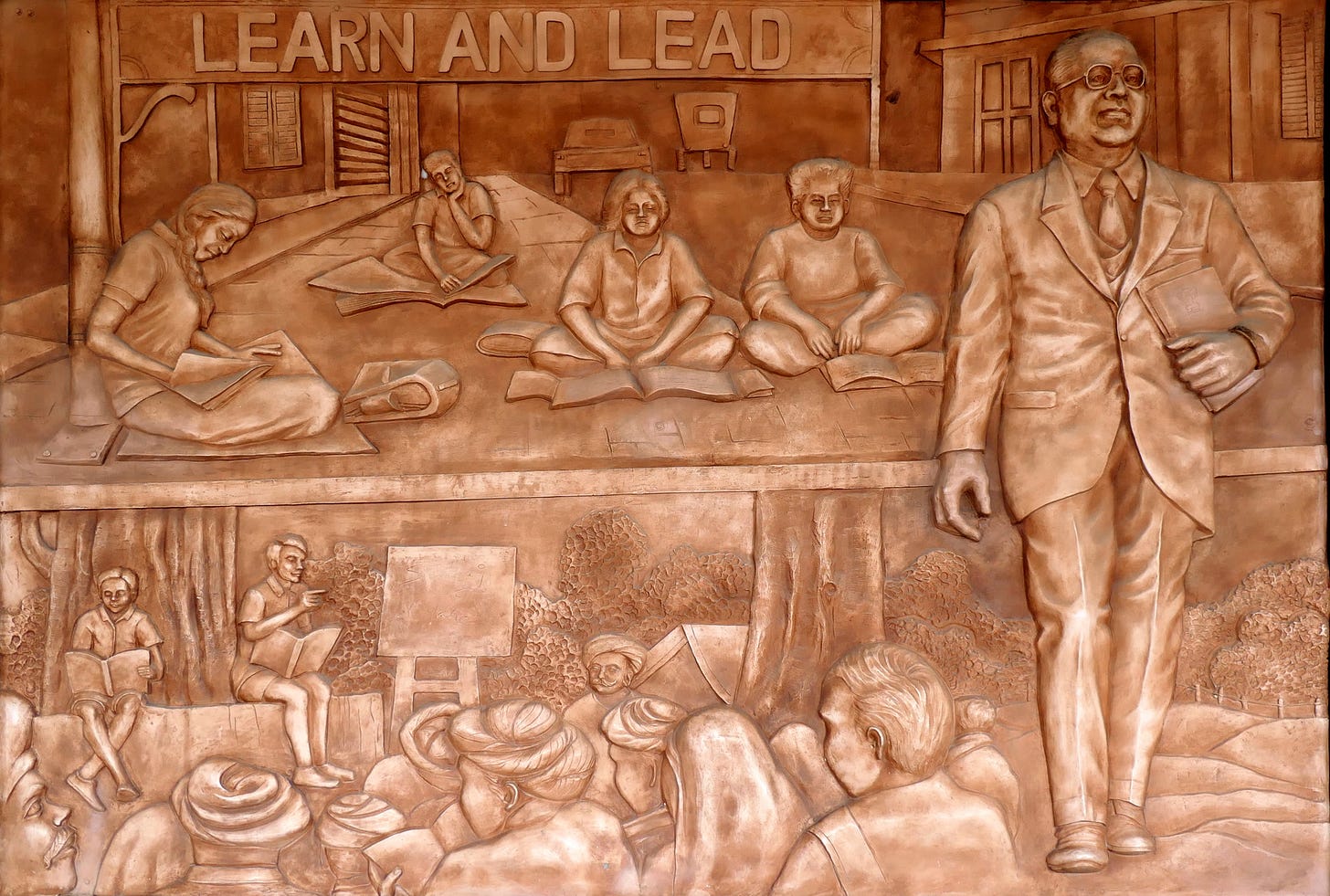

Reading water in a broken pot largely reminded me of a sentence James Baldwin said, “By the time I was thirteen I had read myself out of Harlem”. In Maitreya’s case, he managed to read and write himself out of the shackles of his caste identity. From my priviledged standpoint, writing was simply a talent that must be cultivated and explored for its own sake. But for Maitreya, who in following the footsteps of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, wields the power of the pen to redefine his life.

water in a broken pot is devoid of any sentimentality. Here, Maitreya makes an unflinching commitment to examine his life, both in his best and not so flattering moments. He also expresses his deep gratitude to Babasaheb Ambedkar, his works, and the life-changing impact his ideas have had on him, and Dalits and Bahujans at large. In that sense, the personal is truly the political.

Thank you for reading this far. At the time of writing this essay, Panther’s Paw Publication, an anti-caste publication founded and run by Yogesh Maitreya, is in need of funds for maintaining operations for the next five years. Consider purchasing a set of books to support his work of publishing underrepresented voices. More details here.

The long, painful path towards caste consciousness

Maitreya sets the scene of his early days, growing up in a Dalit basti in Nagpur. His father works long hours as a truck driver, and rarely sees him over the weekdays. He cherishes their occasional father-son weekend visits to the theater and cultivates a love for cinema. That said, it was not a fact of life set in stone. Maitreya recounts how his father wished to become a clerk in the Navy, and even cleared the exams. But Maitreya’s grandmother willed otherwise.

For Maitreya, the feeling of caste-based alienation arrives early in his life. His parents send him to a well-known school, whose students largely came from Savarna families. There was a deep sense of not belonging, a great disorientation while navigating these spaces. A distressing feeling that was so intense that he asked his parents to be transferred to the public school with familiar faces from his basti.

Over time, life gets a lot more harder. Maitreya’s father gets into an accident which forces him to work in a factory at age 15. He recounts his mother working multiple jobs as a maid in houses just to keep the family going. He is an observer of the slow descent of his father towards self-destruction.

Sometimes, I feel: there is no bigger violence than being in ignorance; ignorance kills the enthusiasm to bloom, to grow, to dream as a human being.

It is this ignorance that I imagine fuels his feelings of loneliness, inadequacy, shame, resentment, and bitterness in the early years as he tries to find his way in life. But it is also this ignorance that begins his quest to discover to himself, his history and his rightful place in it.

Finding the language of resistance in the works of Babasaheb Ambedkar

After a series of painful fits and starts, Maitreya settles down to pursue a Bachelor of Arts in Dr Ambedkar College in Nagpur. He is transfixed by the power of the written word. He paints a picture of his solitary figure at the canteen table hunched over a pile of books as students carry about idle banter, his cup of tea getting cold in the corner.

During one of these marathon reading sessions, a well-meaning professor shares a copy of The Annihilation of Caste (AoC) by Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar. To Maitreya, this was a revelation. Below, he describes with reading AoC a life-changing moment that made him feel seen and heard in a way he never experienced before.

The kind of life I had led or had been made to live so far had made me think that there was no history, no beauty or no meaning in it. But no darkness is devoid of history. Before reading AoC I found my life hopeless. I was wrong. I had known Dr Ambedkar as a photo or a story. I was yet to encounter him as a conscience, as a force, as a flame in the darkness. And once I found it, I was no longer the person I had been. AoC laid bare the mental world of caste-society: how it thinks, how it behaves, how it conspires and how it erases the histories of Dalit-Bahujans. In this country, for people, regardless of caste and class, it takes Dr Ambedkar to reach and to be accustomed to their truth. In my life, Dr Ambedkar was the beginning of learning to question. He is an unbeatable energy-when you feel it inside, you change forever.

Through the course of the book we come across his reflections on caste, love, isolation, belonging, the power of language, stories, society, and what true agitation means. For example, Maitreya realized that the strength of the loneliness and isolation that others living as a Dalit in a caste society felt came from the lack of language to express the pain and anguish of living as a Dalit. By reading the works of Ambedkar and other Dalit authors, he also gets the language and lens to understand his father and the destructive toll on his psyche living as a Dalit man. After all, who wouldn't veer towards a breakdown when nobody supports your dreams, your vision for yourself and your loved ones for all your life? When each day is an overt and covert reminder that you will not be treated as a human?

Maitreya’s exposure to Dalit literature solidifies his conviction in the power of language and literature in resisting the absurdity of caste-based oppression. It is an instrument with which Dalits can reclaim their personhood in the consciousness and memory of the majority actively striving to erase it.

Gradually, and surprisingly, their arrival in textual form is being recognised by the world and this community has been reborn in the imagination, both literary and historical, of the world. Text as history and memory-being the most effective tool to keep our sense for resistance against enslavement of any kind alive, proved to be a resurrection from social death for Mahars (Buddhists) and a few other Dalit castes in Maharashtra.

The pivotal moment when Maitreya believes he has to play a part in is when he meets J.V. Pawar, founding member of the Dalit Panthers, and he gets an opportunity to translate Pawar’s work on the Ambedkarite movement.

This experience, along with publishing poetry and columns, are the tools Maitreya wields to unpack his inner world and reflect on it in a meaningful way. And so, he commits to writing and publishing anti-caste literature as a calling. Not just for the pleasure of stringing words for the sake of style or rhythm and telling stories that might make him come across intelligent, but to redefine himself and the communities oppressed under the yoke of caste.

I started writing and translating, not only as an individual, but as an individual who is the sum of his history and people. I started writing with purpose. It made me believe in my engagement with books. I developed the sense that it was through producing stories of my people, who, despite their history of being exploited, had poured their efforts to create the idea of a life based on equality, liberty and fraternity. Without stories of justice, stories of beauty do not make sense in India.

Rebuilding the self, one word at a time

Most of my life, I have been painfully averse to any sort of confrontation and conflict. So much so that I feel squeamish in watching any tamasha going on the street while others keep looking on with curiosity. This is why I have avoided the works of civil rights activists, politically active change makers and reformers. My irrational brain was scared that every line in such works will be pointing an accusing finger at me. I imagined that after experiencing so much hatred from society just for being a certain way, it would be natural for anyone to be hateful by default. This was a sentiment I was expecting from water in a broken pot and I was bowled over by this paragraph that chooses justice, and by extension love and humanity, over hate.

You cling on to hate and it eats you, like termites. Hate neither spares the hated nor the hater. And if hate is seen this way, then, it is not difficult to imagine that the 'agitation' should not take place with hate. The subtext in Dr Ambedkar's philosophy is that 'agitation' is the logical understanding of what is wrong with our being and how that 'wrongness' can be rectified. Agitation is deeply personal; society is the site to exhibit it. Agitation is not a seasonal flavour or a flower (like university campuses in India at present). Agitation is having a restlessness for justice and working towards it to the grave. No agitation is fruitful, or for that matter meaningful, if it is not put into action that changes us from being hateful to compassionate-so we stick to the principle of justice in love and life. Why is justice so essential in India in connection with love?

water in a broken pot is not a perfect memoir. There are times when I wished for more deeper, nuanced takes on his romantic relationships, and how caste poisons the well of love. Nor do we get many of his thoughts on his mother and her foundational role in supporting the family through their most precarious moments.

And yet, it is a book I would like to go back to because of the underlying humaneness of its reflections. I will revisit the several other passages for the insights that moved me and got me thinking. For starters, it really made me question my own faith and the place it plays in maintaining caste hierarchies. Questions which I still struggle with, and I expect will continue to for a while.

What I also enjoyed is Maitreya’s love for reading and writing, which shines through most of the chapters. He peppers his accounts with references to the books he was reading at that time. If it wasn't for Maitreya, I wouldn't have read Lem Sissay’s My Name is Why or Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Nor would I have got back to reading Baldwin’s essays, nor would I have found the courage to pick up Babasaheb’s works and absorb the truths he shares. The discomfort that came with reading his work brought to surface long-standing, deeply-engrained beliefs I didn’t know I even had. It has made me relook at how I engage with caste, examine my own privileges and shake off my passivity around its insidious nature. Perhaps this essay is the beginning to reexamine and break some of these patterns, and reflect on what it takes to live in a casteless society.

Thank you for reading this far. Do consider supporting Panther’s Paw Publication, an anticaste publication founded and run by Yogesh Maitreya. Currently it is carrying out funds for operations for the next five years. Consider purchasing a set of books to support his work of publishing underrepresented voices. More details here.

I am aware that more such films await me in Malayalam and Tamil film industry.

Other must reads include Waiting for a Visa by Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, Yashica Dutt's Coming out as Dalit, Ants among Elephants by Sujata Gidla, and When I Hid My Caste by Baburao Bagul.